This op-ed by Ian Fields, M.D. appeared in SELF. Read the full story here.

I suppose most people don’t remember exactly how they spent their sixth birthday. But tragedy has a way of not allowing you to forget. It was August of 1990. The memories I have of that summer and the months that preceded it are punctuated by small, seemingly insignificant moments with my mother that ultimately changed my life forever. Looking back now, it’s almost like waking up from a dream in which you only remember the bad parts.

My brother and I spent our summer that year at the local YMCA in day camp with our two cousins. We had recently moved in with our aunt and uncle when our mother began to slow and show signs of the cancer that was destroying her body. At 32 years old, she had been diagnosed with terminal, stage four cervical cancer just a few months before my sixth birthday.

This particular day wouldn’t be filled with friends, playgrounds, snack time, naps, and swimming lessons. This birthday would be different.

“Granny will be here to pick you up soon!” Aunt Monika exclaimed.

I was elated. Pulled from summer camp to spend the day with my mom and grandmother. Just me and my two favorite people.

Although I didn’t realize the implications at that point in time, my brother and I had been adopted by my aunt and uncle at the end of July that year, a few weeks before my sixth birthday. My biological father had left my mother, brother, and me shortly after I was born. With incredible foresight, courage, and all of the selflessness only a mother could possess, she signed away her parental rights to ensure my brother and I would be taken care of when her body couldn’t fight any longer.

We had lunch that day at Furr’s Cafeteria, one of our favorite places. They brought out orange Jell-O with whipped cream and a candle. I hate orange Jell-O. I can’t recall whether I ate any of it or not but the memory of orange Jell-O is seared into my mind and never fails to conjure an image of my mom, my grandmother, and that one day in August. I don’t remember much more about that day but I do recall that my mother’s health declined rapidly in the weeks that followed. She was eventually placed on hospice care and moved in with my grandparents.

One month later, we went to my grandmother’s house for dinner. Gatherings at Grandma’s were a staple of my childhood. Birthdays, holidays, random weeknights—all filled with family and Hungarian food. Although weeknight dinners there weren’t out of the ordinary, I knew this one was different. Relatives I had never met—aunts, uncles, and cousins from far out of state—crowded around the table. This would be the last time I saw my mother alive.

I crept upstairs and stood outside the door to her room.

“Hey E, let’s not bother your mom right now,” my uncle Allen said as he scooped me up and carried me into the next room. I had just enough time to scribble “I love you” on a red Post-It note and slide it under her door.

My mother died two days later, surrounded by my grandparents and her siblings in a small room in a house in El Paso, Texas. I never saw her after that final dinner but I still feel her presence in that room to this day.

I can’t say that my mother’s death consciously influenced my decision to become a physician, let alone one who specializes in women’s health, but I would be lying if I said I didn’t believe it had a hand in the way I have navigated through my medical training.

My mother died in September 1990, a short five months after being diagnosed. She was a single mother of two young boys, working as a waitress in a small Chinese restaurant to pay the bills and take care of me and my brother. We had no health insurance. My brother and I shared a mattress in the corner of a room in a desolate trailer in the small town of Anthony, Texas. Despite our circumstances, I never wanted for anything as a kid and I was surrounded by more love than most people see in a lifetime—a credit to my mother and our extended family.

Truthfully I didn’t know the exact cause of my mother’s death until I was almost at the end of my medical school training. I had already made the decision to pursue post-graduate training in a residency program in obstetrics and gynecology—kismet.

I had the fortune of spending some time at Cook County Hospital in Chicago during my residency training. The majority of the patients I saw were uninsured, just like my mother. I saw her in every patient I diagnosed with advanced stage cervical cancer. I saw myself in the faces of their children as I recognized their looks of helplessness. It crushed me. Tragedy has a way of not allowing you to forget.

I miss my mother profoundly and deeply. Each year I struggle with these memories at the end of September when the anniversary of her death rolls around. But I am comforted knowing she left me with the priceless and lasting gift of empathy—to be able to walk with women and their families and say, “I see you. I know you. I’m here.” I also have the opportunity to carry her memory with me and to honor her legacy by advocating for my patients now.

In medicine a great deal of our effort as physicians is targeted at disease prevention. When it comes to cervical cancer, adaptation and implementation of Pap test screening guidelines has led to a decrease in its incidence in the United States as we now have a way to routinely screen for cervical cell changes that may progress to cervical cancer. But now with the advent of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine we are poised to be able to do even more to decrease the incidence of cervical cancer.

When I speak to patients about cervical cancer screening, I also discuss that most of these types of cancers are related to HPV infection. Fortunately in 2006 an HPV vaccine was introduced with the hopes of decreasing the incidence of HPV-related diseases like cervical cancer.

HPV is a common virus that is passed from one person to another through skin-to-skin contact, usually during sexual activity. Although the body clears HPV infection in the majority of individuals without causing any health problems, in some cases it can cause genital warts or cancers of the cervix, vagina, vulva, and the tongue, tonsils, and throat.

When HPV does progress to cancer, it typically takes 15 to 20 years (but under some circumstances can happen in as little as five years). Fortunately there are several ways to lower your chances of becoming infected with HPV or suffering from sequelae of the infection. The HPV vaccine protects against the nine most common strains of HPV that are associated with genital warts and cancer. This vaccine can be administered as early as age nine and is recommended for teenagers of all genders at ages 11 to 12. It is a two-dose series; the second dose is given six months to a year after the initial one. HPV vaccination is recommended for people up to age 26, but the FDA recently approved the HPV vaccine for use in individuals up to age 45. The vaccine has been shown to be safe and effective in the prevention of HPV infection and has the potential to decrease cervical, vaginal, vulvar, and oropharyngeal (throat) cancers.

It is important to note that regular condom use can also help protect against exposure, but it doesn’t fully eliminate the risk since HPV is an infection that can be transmitted through skin-to-skin contact—even on parts of the genitals not covered by a condom. Even if you have been vaccinated, routine screening with Pap tests starting at age 21 is recommended to check for changes in the cells of the cervix as well as HPV infection. You can learn more about how often to get screened for cervical cancer here.

I can’t help but think of my mother when I’m counseling patients about the benefits of vaccination against HPV. What would I do if someone like my mom was sitting across from me in the exam room asking my advice—a single mother with two children, no health insurance, and working full-time to provide for her family. My advice to that patient (and to any patient) would be simple: Get the vaccine.

There was no vaccine available for my mom when she was growing up in the 1960s. It is hard to live life based on conjectures like what if or if only but I can imagine that had my mother had the chance to receive the HPV vaccine—one that can prevent cancer—she might still be here with us today. And that certainly would have changed my life.

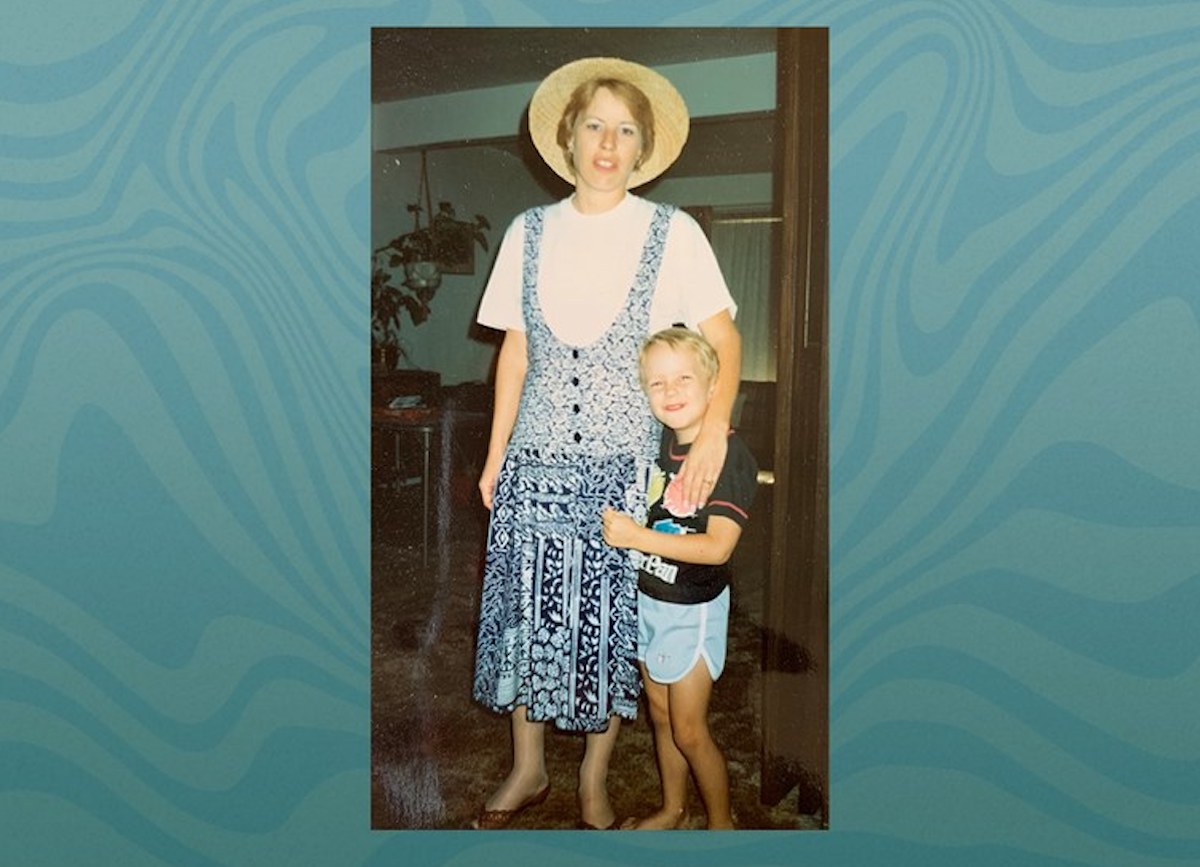

Photo courtesy of Ian Fields.