This article appeared in Forbes. Read the full story here.

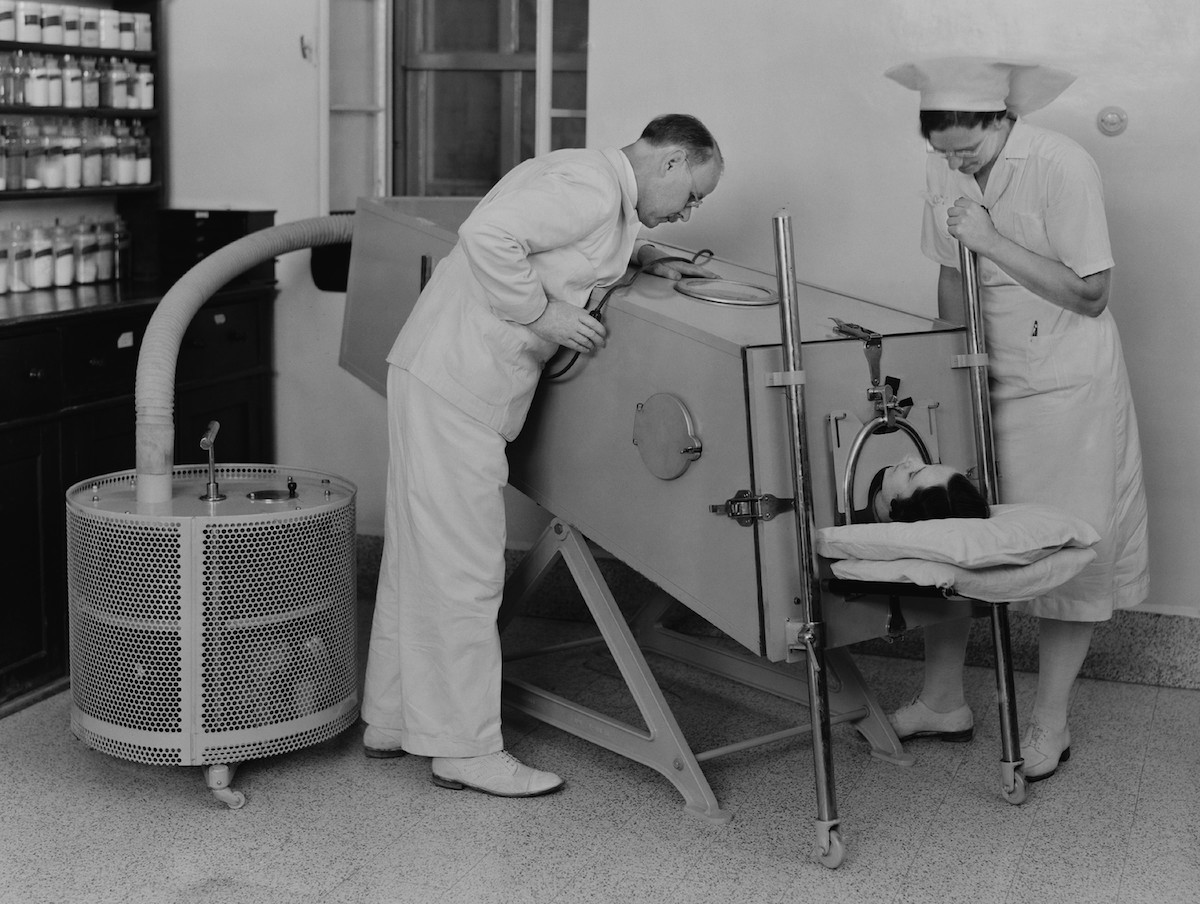

The iron lung defined a generation’s experience with polio. Today, its metal bulk embodies the horror of the disease, but in the 1950s, it saved hundreds of lives. Its inventor wasn’t a doctor; Philip Drinker, born on December 12, 1899, was an industrial hygienist – an engineer who specialized in air safety issues like ventilation, pollution, and dust in industrial settings like hospitals and coal mines. And the invention that made him famous was really just a side project early in his 40-year career.

“As time passed, Phil began to look on what he called ‘all that fuss about the respirator’ as out of focus. He said that in 40 years’ work at the [Harvard] School of Public Health, the ‘damn machine’ was only one thing, and it just happened,” his sister and biographer Catherine Drinker Bowers later wrote in her book Family Portrait.

It was an ordinary day in the late 1920s, and Drinker had stopped by a children’s hospital to consult on a problem with its air conditioning system – not to rescue the dying children with paralyzed diaphragms, unable to even take a breath after the polio virus had its way with their spinal cords. But the sight stayed with him.

“He could not forget the small blue faces, the terrible gasping for air,” Bowers. Drinker also realized that victims of coal-gas poisoning, and a handful of other conditions, needed a similar solution. By 1828, he had designed and built a machine to replace patients’ paralyzed diaphragms: a negative-pressure ventilator, although the world would call it an iron lung. The pressurized metal cylinder would surround the patient. When the air pressure inside dropped, it would cause the patient’s chest to expand, drawing air inward. Increasing pressure in the cylinder would press on the patient’s chest, gently forcing an exhalation.

When Drinker and his colleagues carefully placed an 8-year-old polio victim in the cylinder, she began breathing normally (with the machine’s help) within seconds. By the 1940s and 1950s, as the polio epidemic in the U.S. and elsewhere reached its devastating peak, rows of iron lungs filled hospital wards, keeping paralyzed patients alive. Most young patients with respiratory paralysis only needed to spend about two weeks in the machine, but some relied on – and lived in – the iron lung for years or even decades.

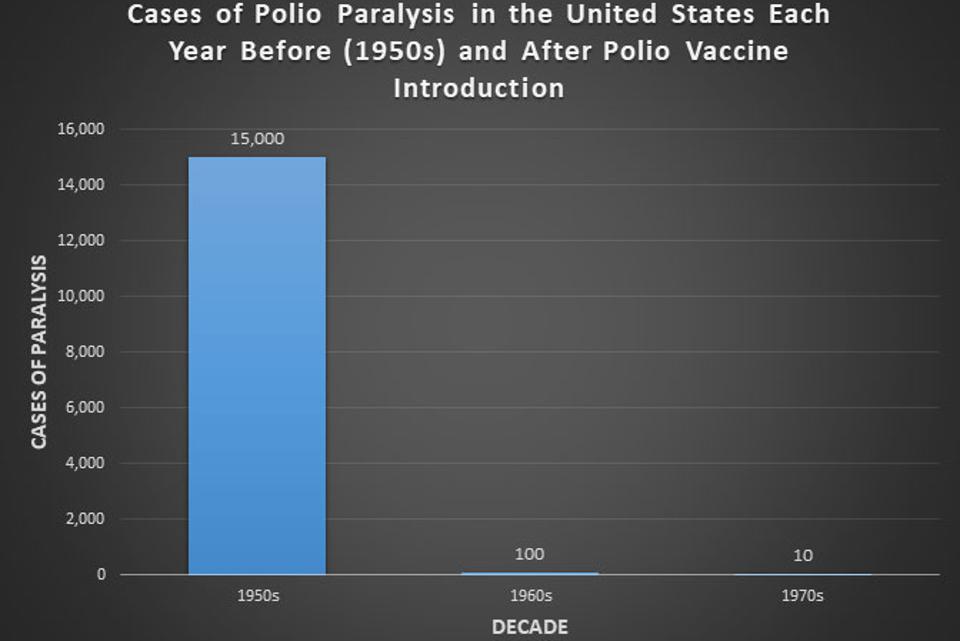

Polio cases dropped dramatically with the introduction of the vaccine in 1955, but we need … [+]

CDC

Today, only 3 people still live in aging iron lungs, kept running by custom-fabricated parts, sometimes the work of local maker communities. But once, the ominous metal cylinders were safe havens for hundreds of patients every year; in 1951, about 1200 people relied on iron lungs at any given time.

As the epidemic came to an end, so did use of the iron lung. In the 1940s, polio paralyzed about 35,000 people each year. By the 1950s, that number had tapered to 15,000 new cases each year – and in 1955, the tide turned abruptly. Humanity had acquired a new weapon against the paralyzing disease: a vaccine.

Doctors began vaccinating children and adults in droves, and parents lined up eagerly to protect their children against polio. After all, what’s a quick needle-stick compared to weeks, months, or years fighting for life in an iron lung? By the 1960s, less than 100 people a year contracted polio in the U.S., and by the time Philip Drinker died in 1972, new cases dropped below 10 a year.